The cruelty of Cordelia’s death is completed by the knowledge that it might have been averted. Human brutality can be casual, but it is the nonchalance of fate that makes pain hardest to bear. No one could understand why the Germans should have burnt down the stable with the cows and the people inside, but perhaps it was only because they had some petrol to throw away. The mayor’s stable was now a heap of ashes, and you still seemed to hear the lowing of the cows and the shrieks of the shepherd boy calling to his mother. The Germans had freed the hostages they had taken that day but then during the night they had come back and taken some more, two sons of the dressmaker’s and a sister of La Maschiona’s seducer and a shepherd boy of 14 years old, and they had taken them into the mayor’s stable and had poured tins of petrol over the stable and set fire to it. Cenzo Rena thinks that if he says he killed the soldier, the hostages will be set free.

A German soldier has been found dead in a stream outside the village of Borgo San Costanzo where Cenzo Rena lives, and hostages have been taken.

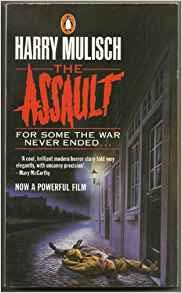

In Natalia Ginzburg’s novel All Our Yesterdays, first published in Italy in 1952, the Germans shoot Cenzo Rena for much the same reason as they shoot the Steenwijks in The Assault. It is the Communists who have assassinated Ploeg, and the body originally lay outside the Kortewegs’, the house next door, but Mr Korteweg and his daughter crept out and moved it before the police and soldiers arrived. The Germans shoot Mr and Mrs Steenwijk and their son Peter and burn down their house, because Fake Ploeg, chief inspector of the Haarlem police, has been found dead outside their front door. He never sees his mother and father and brother again. As the house collapses ‘under a fountain of sparks as high as a tower’, Anton hears a burst of machine-gun fire. Standing around in the dark and the cold, ‘laughing and talking’, members of the Grüne Polizei warm themselves at the fire that is consuming Anton’s world, where only a moment earlier, quiet and secure, he had been playing ludo with his mother and brother before going up to bed. This is something that is incurable and will never be cured no matter how many years go by.’ Thirty-six years went by and in 1982, in Holland, Harry Mulisch published De Aanslag, a novel in which Anton Steenwijk, aged 12, watches his family home, the house he has grown up in, reduced, in a matter of minutes, to rubble, by the action of a couple of German grenades and a flamethrower. ‘Il Figlio dell’Uomo’, ‘The Son of Man’, an essay by Natalia Ginzburg written in 1946 for the paper Unita, begins: ‘There has been a war and people have seen so many houses reduced to rubble that they no longer feel safe in their own homes which once seemed so quiet and secure.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)